This post was originally given by Emily as a paper for DePaul University in Chicago’s Pop Culture Conference: A Celebration of Star Wars on May 4, 2024.

From its origins, Star Wars has been centrally concerned with our human struggle against the Machine. As early as 1973, Lucas wanted to depict “a large technological empire going after a small group of freedom fighters.”(1) Darth Vader is an emblem of encroaching technological domination and the loss of individual choice, vulnerability, and transcendent connection with others; the emblem of his Empire is a cog. But another Machine-man has, of late, come to dominate the franchise: the Mandalorian. Stories of Mandalorians reveal a rich heritage of belief and tradition. Yet they perennially hover on the brink of extinction—often due to their own technology and warlike ways. From Din Djarin to the Fetts to Sabine Wren, Mandalorians offer a nuanced—even ironic—exploration of Star Wars’ central concern with technology and how to use it without becoming it.

Many sources inform Lucas’ preoccupation with machine existence in Star Wars. One is arguably most important: Arthur Lipsett’s 1963 art-house short for the National Film Board of Canada entitled 21-87. It is a mind-blowing 10-minute experience, available on the National Film Board of Canada’s website. Lipsett was a scavenger who pieced together his colleagues’ rejected material into highly symbolic montages. 21-87 juxtaposes images and audio of modern, machine-based existence (always absurd or horrific) with those of human suffering and of humans in natural, dignified states of wonder. The film derives its name from a recorded discussion about the mechanization of society. A voice, arguing mechanization fulfills the human desire to “fit in,”(2) says, “And somebody walks up and you say, ‘Your number’s 21-87, isn’t it?’ Boy, does that person really, uh, smile.”(3) This audio is repeated at film’s end, leaving the impression that the Machine Age will triumph—if we let it. Lucas watched the film two dozen times as a student, fascinated by its grim message about the Machine age as a threat to our humanity, yet also the potential of nature, art and transcendent spiritual connection to overcome it. (In the film, Lipsett featured recorded dialogue calling such spiritual power and connection “a Force… or something,” and this phrase seems to have stuck in Lucas’ mind.)

I give a much fuller explanation of Lipsett’s film and its messages in the 2023 anthology I edited with Amy Sturgis for Vernon Press. In my chapter, I trace the major ways Lucas teases out Lipsett’s ideas in his Original Trilogy and in prequel material. And 21-87, I argue, remains important in the post-Lucas era, especially as expressed in Finn, also known as FN-2187, and in the Narkina 5 arc in Season One of Andor. But even before Andor, the first chapter of The Mandalorian presented as a study in this theme’s enduring influence in Star Wars. The main character, known only as “Mando” or “the Mandalorian,” is a lone, stone-cold killer, intent on nabbing his bounties, warm or cold. He is faceless, machine-like in his appearance and efficiency; he speaks only out of necessity. He’s not political—he doesn’t care who the client is; this machinic mercenary goes wherever his violence will be compensated.

The collective nature of his moniker rubs ironically against his singularity in that first episode. He is a lone wolf, but he is all the Mandalorians. As the episode progresses, Mandalorian comes to mean a Man-of-Lore, steeped in a rich, mythic tradition—alluded to by Kuiil as he urges his taming of the Blurrg. We all need such encouragement sometimes. Star Wars was devised, in part, to “update” mythological motifs(4) into more humanistic language(5) anyone can feel inspired by. Lucas had lamented, from his college days, that there was “no longer a lot of mythology in our society”(6) (a preoccupation of Arthur Lipsett as well). Just as the Original Trilogy projected from Luke Skywalker’s point of view, The Mandalorian projects from Mando’s, and we project ourselves onto his image. (This invitation is amplified in Episode 3 when he comes out wearing a full suit of mirrors.) The Mandalorian really feels like Star Wars because, as the original films did, it invites the audience to be spiritual beings, to be Luke Skywalker, to be a Mandalorian, a Man-of-Lore.

But as 21-87 espoused, in the modern age, we spiritual beings are in danger—in danger of becoming faceless cogs of the Machine, and religion is not a silver-bullet solution. The show gradually reveals that Mando in fact does not represent all the Mandalorians, and his religious extremism plays with the notion, also found in prequel material, that religiosity is not the measure of one’s connection with the transcendent realm; too often it is an impediment. Patrick Tiernan reminds that the word religion comes from the Latin verb religo/religare, “to tie up or bind”(7); Mando binds himself tightly to a harsh way of life, epitomized by his refusal to show his face. The inflexibility of his religious belief dehumanizes him.

But the moment he gazes upon the Child—a pitiable yet mysteriously luminous being—his instinct toward myth and transcendence overpowers his sense of duty, and he spontaneously kills the machine, or at least the one next to him, IG-11, to preserve the Child. The image of Mando and the Child’s fingers touching alludes to Michaelangelo’s The Creation of Adam; here the Child imparts life to the Mandalorian—and a new perspective that will re-direct his path and that of his people. This is the Way—the way that awakens the Mythosaur and eventually returns Mandalorians to their home and to unity.

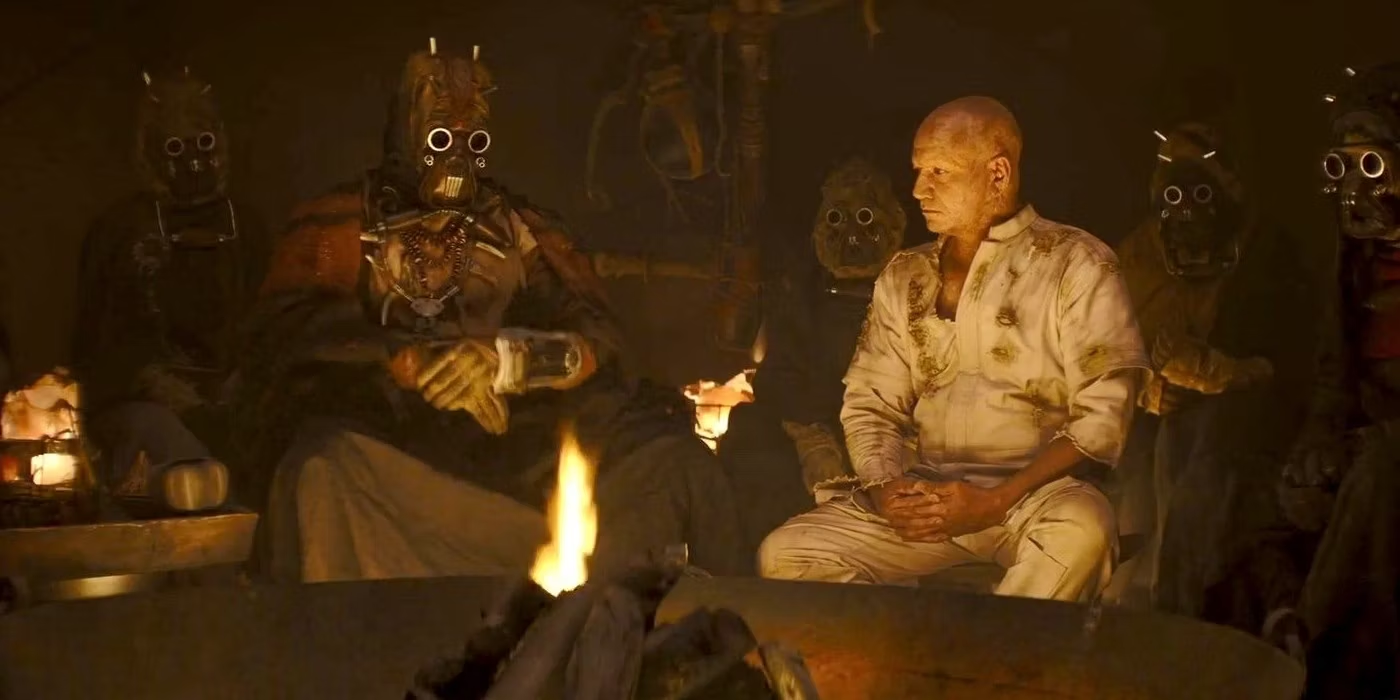

Another Mandalorian expresses this same longing for spiritual communion. The Book of Boba Fett traces the burgeoning humanity of a yet more infamous Mandalorian bounty hunter. No one will ever accuse Boba of being a “true believer,” but his honor is apparent. Far from the sociopathic figure we saw in Empire, Fett now values integrative work, partnership, community—values he gleaned from the Tuskens after his escape from the Sarlacc pit. Experiences of transcendence come also from inclusion in a loving community; Chapter Two of Book of Boba, “The Tribes of Tatooine,” demonstrates this quite movingly. And the tragic loss of Boba’s Tusken tribe does not embitter him the way the loss of his father Jango did. Even in the midst of his grief for the Tuskens, Boba’s compassion spurs him to help others, like Fennec and Mando, and he builds community with them. Boba Fett may never quite be a Mandalorian—a Man of Lore—but he gets surprisingly close. Pinned down by the Pike Syndicate in the series finale, Din pledges to die with Boba in the name of honor, per the Mandalorian code. Boba says to him, “You really buy into that bantha fodder?” When Mando says he does, Boba answers, “Good.” One need not personally believe fantastical things to commit to a higher purpose. Whether you can bring yourself to believe this bantha fodder or not, there is power—“a Force… or something”—in belonging to a tribe.

Perhaps no Mandalorian embodies these ideas better than Sabine Wren, who first appeared in animation. Now featured in the live-action show Ahsoka, her arc has gotten interesting. The daughter of a warrior mother loyal to the Empire and an artist father imprisoned by the Empire, Sabine lives a dual existence. She attended the Imperial Academy until she realized the Empire’s genocidal plans for her own creative inventions. Lena Richter says Sabine’s character points up the more artistic, creative side of Mandalorian culture; her chosen appearance challenges stereotypes about Mandalorians and symbolizes her “struggle with her identity.”(8) She “paints and re-paints [her armor] constantly in a way that reflects the events of the past and the way she views herself,”(9) until her armor becomes more and more traditionally Mandalorian, with jetpack, vambraces, and the Darksaber, the mythic weapon of the only known Mandalorian Jedi. This storied weapon symbolizes the joining of two worlds—Mandalorian and Jedi, and Sabine becomes the embodiment of this joining, as she discovers her ability to use the Force—not for revenge or domination, but to save her friends and to give the Republic a fighting chance.

The Machine is never defeated in Star Wars. Even in the age of the New Republic, the threat of that “technological empire” George Lucas first positioned as Star Wars’ antagonist still lingers. Mandalorians like Din Djarin, Boba Fett and Sabine Wren offer poignant expressions of the tensions of our modern life as humans under this constant threat. But as Star Wars—still inspired by Arthur Lipsett’s 21-87—shows, our instincts for transcendence, for shared mythology, for numinous community will also endure. The Mythosaur has awakened: This is the Way.

Happy Star Wars Day! And May the Fourth Be With You…

- Chris Taylor, How Star Wars Conquered the Universe (New York: Basic Books, 2014), 88.

- Ibid., 44.

- 21-87, directed by Arthur Lipsett, 1963.

- Taylor, How Star Wars Conquered the Universe, 84.

- Ibid, 71.

- Lucas, quoted in Ibid, 43.

- Patrick Tiernan, “Paradox of Faith: The Way of Din Djarin and Kierkegaard,” in Star Wars and Philosophy Strikes Back (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2023), 230.

- Lena Richter, “Of War, Peace, and Art: Mandalorian Culture in Star Wars Television,” in The Transmedia Franchise of Star Wars TV, ed. Dominic J. Nardi and Derek R. Sweet (Cham, SZ: Palgrave MacMillan, 2020), 167.

- Ibid.